Three generations of open war between the Vlemish in the south and the Plenor in the north had wrecked the once-fertile hills of Belrond. Battle-lines waxed and waned like sea-waves, wiping clean the landscape and driving its inhabitants to seek furtive shelter in cracks and dark places. Nobody could remember how the war had started, nor could anyone imagine that it would ever end. There was no question of allegiance — neither army attempted to ally with the hill people, who seemed to exist only to raise stunted crops to be eaten, half-grown, by pillagers from one army or another. Food was not all they took — if the brigands fell upon a Son of Belrond, he was killed for sport. Belrond’s captive daughters came to worse fates.

It was in this climate of despair that a man came to offer his services to the Fathers of Belrond. Fifteen hands across at the shoulders, tall enough to fill the garrison’s archway, and carrying a mallet the size of a birthday breadloaf, he called himself Mard Hammerhand. He was not a native of Belrond, nor were his features familiar to anyone who had traveled abroad, but his ready smile and booming laugh dissolved all barriers of mistrust. The Fathers were quick to offer the warrior the few things they still possessed in return for his protection. Mard roared with amusement, slapping the nearest Father on the shoulder and nearly bowling him over. “Aye, this whacker will knock helmets into slop-bowls easy enough, but I’d prefer to see something made for once! I’m a quarry-man and a builder by trade, and you’re sitting on enough granite to bung up Thrond’s arsehole!”

The Fathers were doubtful, but a lull in the fighting had left the younger men and women of the hills in a comparatively energetic mood. Above all, Mard Hammerhand had a plan — something novel to the Belronders, who had forgotten the future existed. Even better, the plan leveraged the two things Belrond had in abundance: granite and topography.

The entire kingdom (if the tattered remnants of Belrond could still be called such a thing) set to work quarrying stone and constructing a keep upon Greymount, its tallest hill. The keep’s bastions rose quickly, not least because of Mard’s impressive (some would say impossible) physical strength: in the time it took the strongest man to drag a granite half-stone to the foot of the keep, Mard would sail past five or six times, a whole stone tucked under each arm, hallooing cheerfully or making a ribald joke on each pass. He tossed the stones into place as though they were pillows and kept working into the night, long after the others had dragged themselves home for their thin evening gruel.

By Spring, Greymount Keep was complete. It was a handsome thing, with three crenelated towers, the tallest topped with a trebuchet that had been cobbled together from river-lumber. The fastness was finished just in time for campaigning season, as watches had been set for only a few days when the first army appeared on the horizon. The Belronders retreated to their keep and many wept, for though they were willing to die, they had few illusions about their fighting skills.

Mard looked on them with a raised eyebrow, then hefted his hammer onto his shoulder. “Come on, lads! Think on all the busted thumbs and sprung groins you suffered putting this little castle together last Winter! Surely you won’t suffer those pissants to dismantle it so quickly!” The words meant little to the ragged band, but Mard’s tone filled them with an otherworldly confidence, and they took up their swords and bows with a shout.

The battle ended quickly, and not in the way the Belronders had expected. Many felt as though it had been a dream. First came the advancing ranks of pikemen, then the boom of war trumpets, and then Mard surging forward with his whirling hammer, mowing his enemies down like wheat. Every son of Belrond was filled with battle-rage, and they made quick work of their enemies (this time, Vlemish), who had grown accustomed to easy prey on the hills of Belrond.

During the celebration that followed, all present called for Mard to be made King of Belrond (which had never before had a king). Mard blushed and declined. “You lot think that was the end of your woes? They’ll soon be back with bigger armies and siege engines. No, I’m a captain at best, or maybe a colonel, if you’re feeling charitable.” The Fathers, visibly relieved at having avoided demotion, insisted on making Mard a general, to which he grudgingly assented, on the condition that if anyone saluted to him, they’d get a hammer-handle up their arse.

In mid-Summer, the armies of Plenor fell upon Greymount Keep. Apparently, no word of the earlier battle had reached them, for in their surprise they were routed even more quickly than the Vlemish. Mard furnished the battle’s most memorable feature, throwing his hammer from nearly a league behind the retreating cavalry and completely destroying the enemy general, along with his horse.

Mard Hammerhand had never been officially made a peer of Belrond, but by now every Belronder saw him as their brother, their father, or their son. When harvest time came and the store-rooms were filled with wheat and barley for the first time in human memory, Belronders wept at the plenty and approached Mard at random to hug him and shake his hand.

Meanwhile, the Vlemish and Plenor met under a banner of truce, having each lost an army in Belrond. All agreed that it was necessary to annihilate Belrond’s new captain and keep so that they could get back to the business of fighting each other. Plans were drawn up for an allied army to attack Belrond in the following Spring, and special squads were trained to target and kill Mard Hammerhand.

When the battle came, Mard once again marched at the head of his small army. His eyes gave no hint that he was worried by the long rows of advancing siege towers, or the rumbling columns of dragon-faced artillery. He waded into the enemy throng like a child into a pool, towering above his scattering enemies. His companions showed no fear either, and the sight of the Belronder army tearing through ranks of crack soldiers struck fear into the hearts of Vlem and Plenor.

The sun sank low in the sky, and until the last moment, it looked like the day would belong to Belrond. Preparing to crush a supply train, Mard was caught off guard when one shabby wagon shed its skin to reveal a ballista, crewed by strange men wearing black armor. Mard’s brothers screamed for him as the machine fired a salvo of iron missiles into his chest, hurling him to the ground. As his seconds dragged him back to the keep, he spoke his final words: “Let me rest for a while in the highest tower. I want to see the sun rise once more.”

During the night, while the invading army made camp beyond the walls of the keep, all of Belrond despaired. A bed was brought up to the tower, and Mard’s body was laid upon it and covered with flowers. Families held one another and wept, for they knew that without Mard Hammerhand, the next day would bring oblivion. The Fathers gathered around his deathbed and prayed to the All-Father to intervene in the coming battle. In their exhaustion, they fell asleep at the foot of the bed, covered in tears.

When they awoke, they found that Mard had vanished. Only his bloody armor remained upon the bed. “He has been stolen in the night,” they cried. “He has been defiled!” But their lamentations were cut short when they saw that their sons had already taken to the battlefield below, and in the soldiers’ shuffling gait was foreshadowed the total defeat of Belrond. The opposing ranks of Vlemish archers unhurriedly nocked their arrows, preparing for a final death-salvo.

Then a deep rumble shuddered the ground. The Belronders within the keep stumbled and fell, for the building had begun to collapse around them. Outside, a cheer went up among the Vlemish and Plenor for the success of their sappers, who had apparently tunneled beneath the Belronders’ wall during the night.

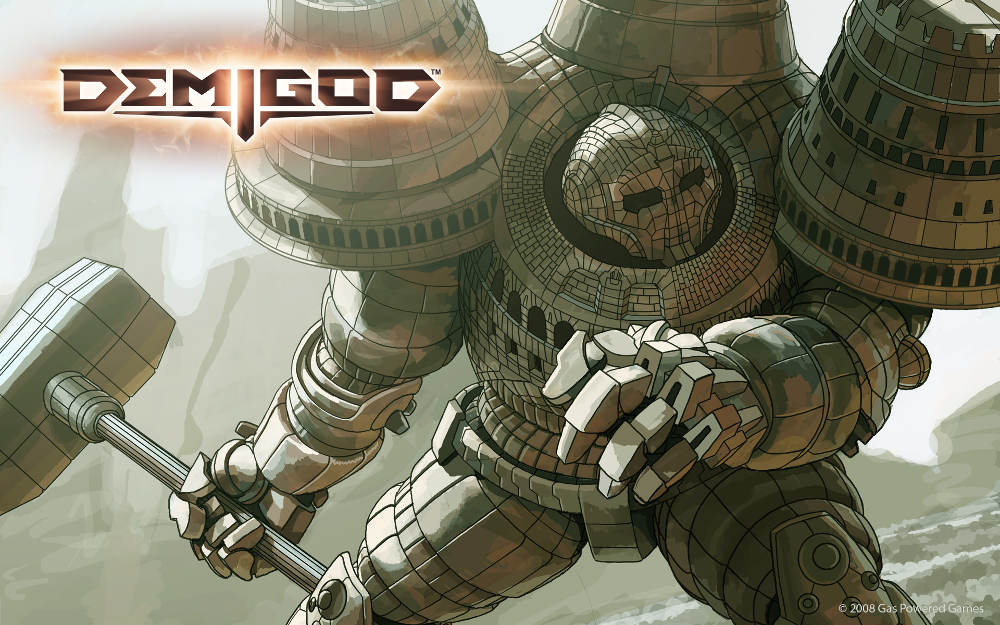

Somehow, the keep did not fall. Towers began to rise, bastions uprooted themselves from the ground, and the keep reshaped itself into something taller. Where side towers had once stood, now resolved stony arms, and in the center of the main tower, where Mard Hammerhand’s deathbed still lay, now sprouted something like a head. The keep had become a living thing, with trunk-like legs and hands the size of haylofts. With one of these, it reached into the ground and uprooted a monolithic slab of stone. With the other, it uprooted a stand of trees and jammed their trunks clean through the great rock in a single violent motion. Standing behind the bewildered army of Belrond was a stone giant, and in its hand was a hammer.

When the last remnants of the invading army had been stamped out on the other side of the river, the stone goliath strode back to Greymount, turned to face the still-rising sun, and settled back into place. Every stone returned to its proper spot, and all within the keep were safe in their rooms, uninjured.

When the Fathers of Belrond returned to Mard’s deathbead, his body once again lay among the heaps of daffodils. On his face, however, there was a wry smile.

In all the years that followed, Mard’s body was never moved, and his smile never faded.